| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

HEREFORD PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL 2009 Various venues, Hereford

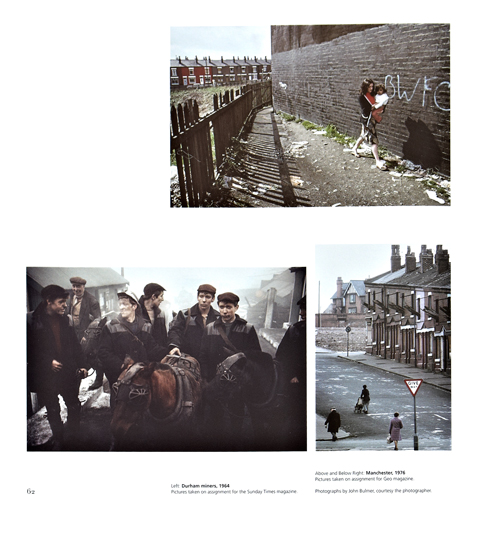

There was a time in the late 1990s/early 2000s when the Hereford Photography Festival was a beacon in UK photography. Then Britain’s only non-commercial photography festival, it managed year after year to stage shows by substantial photographers such as John Blakemore, Tom Stoddart, Simon Norfolk, Tom Hunter and Daniel Meadows, alongside lectures and workshops by major figures such as Paul Hill and Fay Godwin. All this took place in a small provincial city three hours from London, with few suitable venues and a limited local audience for contemporary photography. But a few years ago the festival began to lose its way. The quality and range of exhibitions declined, and the festival’s original focus on British documentary photography was largely abandoned with no alternative put in its place, culminating in a disastrous two years under Paul Wombell, the distinguished former Director of the Photographers’ Gallery in London. His tenure was entirely given over to South African photography, much of it admirable in itself, but a surprisingly narrow subject – especially spread over two years – for a festival that needs to work hard to attract its audience. Meanwhile, the smarter, better-connected, more media-friendly Brighton Photo Biennial was launched in 2003. Last year the Arts Council, the festival’s chief paymaster, read Hereford the riot act. The upshot is that a new director, recently appointed, is working on relaunching the festival properly in 2010. This year’s exhibitions were staged as an interim festival, a limited holding operation guest-curated by Bridget Coaker, the night picture editor of The Guardian. Fortunately for Hereford, Coaker organised one of the most interesting festivals seen in the city for years. Its principal show was a retrospective – one might say rediscovery – of John Bulmer, one of Britain’s leading photojournalists of the 1960s–70s and a central figure on The Sunday Times’s groundbreaking colour supplement when it first launched. Bulmer has since largely dropped from view because he gave up stills photography for documentary film-making in the 1970s, he was not associated with historic events such as Vietnam, and no books were published of his work. Such is the throwaway world of journalism. Bulmer’s work has a global reach but the bulk of the work in this show was made in the industrial cities of the Midlands and northern Britain. It avoids hard news stories in favour of documentary records of working-class daily life, producing what are now fascinating time-capsules of information about a past that is just out of reach, even if many of its material components are still with us. Bulmer’s photographic style also represents something of a vanished past – an era when formal composition in photojournalism was still regarded as a virtue. As his work developed, he seems to have taken an increasingly detached approach, setting up a carefully designed stage in the manner of Cartier-Bresson and waiting for the event to unfold upon it. His instinct for composition is underpinned by an assured and pioneering use of muted colour as a structural device at a time when colour was a novelty in journalism. In his 1977 picture of a mother and child walking through a litter-strewn alley in Manchester, for example, bands of blue-grey and brown radiating from the vanishing point provide a framework in which the strongest colour draws our attention directly to the woman’s T-shirt, echoed by a single red-painted house-front in the background. Graffiti for Bolton Wanderers FC gives us the location. Beyond the broken railings we glimpse a rough, grassed-over hollow, possibly a WWII bomb crater still unreclaimed in this impoverished area after more than 30 years, and what seems to be heavy-duty buttressing of a building just out of view. The child (black) stares directly at the camera, signaling the presence of the photographer, while the mother (white) strides on, head down, indicating a place where it is advisable to pay no attention to strangers. The picture is as revealing as it is striking and beautifully made. Bulmer’s work suggests not so much a critical engagement with contemporary society and politics – in the manner of Frank or Jones Griffiths – as a celebration of the world, including working-class Britain, as a tableau of curiosities. His pictures of the North dwell mainly on the stock subjects of headscarves and curlers, washing in the streets, industrial grit, terraces, community pubs, miners with pit ponies and so on. However if his work lacks something of an individual critical voice, it is remarkable how often it recalls, or even prefigures, much better-known work by other photographers – either back to Brandt and Bourke-White or forward to Killip, Graham Smith, even Struth – and it easily holds its own in such company. His 1960 photograph of a bent and ragged old woman cleaning her gatepost in Nelson is no less iconic an image of grinding poverty than Brandt’s celebrated coal-searcher returning to Jarrow in 1936. Bulmer’s work deserves to be better known. Let this be the start. The festival’s other major show was a group exhibition of images of children, staged to explore how photographers are handling the increasing legal and social difficulties that surround this subject. If not entirely successful in this respect as most of the work featured teenagers (much less contentious than younger children), it at least provided an opportunity to show some of the delightful and original stagings of Jan von Holleban (Dreams of Flying) and Vee Speers (The Birthday Party) – exactly the sort of eye-opening photographic art that deserves the widest possible audience. If Hereford is to thrive again as a full-size festival it will need – among other things – to establish a clear distinction between itself and Brighton. The south-eastern biennial has entrenched itself as an international, themed event. Hereford might be wise to take a different tack, perhaps unthemed, like the great annual festival at Arles, and focused on British photography; and to show at a different time of year. Any attempt to go head-to-head with Brighton, as has been mooted, could end in the obliteration of one or other festival. All lovers of photography in Britain will be sincerely hoping that that does not happen. |

|

|---|---|