| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

HEREFORD PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL 2010 Various venues, Hereford

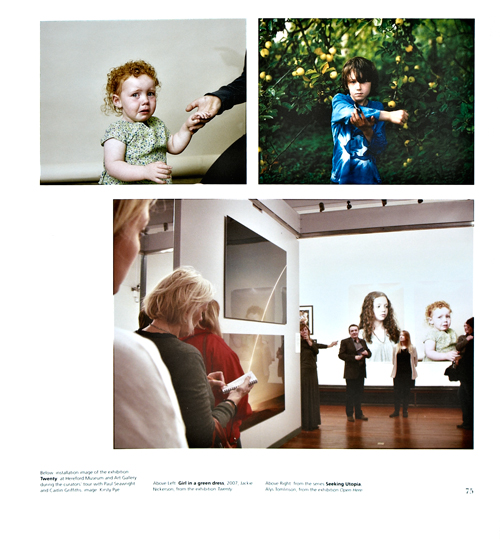

After a few years of drift, a thorough deck-scrubbing ordered by the festival’s paymaster, the Arts Council, and last year’s limited forays into shallow waters, it was bound to be interesting to see how well the Hereford Photography Festival sailed this year under new management led artistically by curator Caitlin Griffiths. On one level the festival was a great success – and for its supporters, a relief. A great deal of strong work was shown across five main venues, most of it new or little-known, including pieces by several big photographic names. Bucking the trend of some previous Hereford festivals, there were no significant weak spots, no examples of curatorial or photographic amateurishness. A programme of artist’s talks, curator’s tours and a conference suggested a festival with rudders mended and fresh ballast in the hold. The festival’s main show, Twenty, took advantage of the event’s 20th birthday to display new work (three or four pieces each) by 20 significant photographers who have exhibited at Hereford over the years. Curated by Paul Seawright, the exhibition indicated the range and energy of contemporary photography, from the documentary landscapes of Paul Shambroom and Simon Norfolk to the poetics of Roger Ballen and Paul Hill, and from the portraiture of Shelby Lee Adams and John Bulmer to the satirical works of Martin Parr and the neo-Pictorialism of Liza Dracup. The decision to show new work avoided the trap of nostalgia, with its implication that the festival’s best years might perhaps be over, and underscored the festival’s record of backing winners. The other major exhibition, Open Here, an open-submission show, similarly presented a few works each by 23 widely differing photographers. Stand-out contributions here included Alys Tomlinson’s luxuriant portraits of inhabitants of alternative communities from Seeking Utopia, Vincent Mundy’s exquisite series Searching for Bessarabia, on the Romanian-speaking but Russified eponymous lost state,and J Carrier’s coolly elegant landscapes of Israel and the West Bank from No Such Thing – but everything here was worth seeing. The question is, was it enough? How should we measure success for an event such as this? Many will be satisfied that the festival brought excellent photography to a small provincial city with little alternative exposure to first-rate contemporary art. If the gallery spaces seemed a little quiet during my visit, they were no quieter than those in any other regional town. Yet it was hard to escape a nagging sense of disappointment, a feeling that a photography festival – Britain’s oldest, and for a long time our only annual photography festival – should be doing better than this. The very least one might hope for is to be noticed. Yet, besides the internet, national media attention was virtually non-existent. You cannot be a significant national event if you have next to no national attention. Location should not matter. Connoisseurs of early music know they can go to festivals in York or Brighton; for contemporary music, they have Huddersfield. Jazz lovers travel to Brecon or Cheltenham. For books, there is Hay. Everyone knows about Edinburgh, and the rock and pop festivals in out-of-the-way places like Glastonbury. All these festivals are covered, some even sponsored, by the national media. Must photography, the most pervasive, complex and fascinating of the visual arts, always be seen as a fringe activity, a minority interest? Major European festivals, such as the Rencontres d’Arles or Visa pour l’Image at Perpignan, always attract an international audience. Closer to home, a comparison with the biennial Brighton Photo Festival, which ran one month earlier than Hereford this year, is unavoidable. The work shown there was arguably no better than at Hereford. But being closer to London, better connected, guest-curated by Martin Parr this year, associated with the Sunday Times Magazine, and (crucially) the first of the two to take place, Brighton attracted numerous national newspaper and magazine reviews including a multi-page feature in British Journal of Photography. From a festival wishing to be taken seriously as a national event, Hereford’s decision to run a few weeks after Brighton showed breathtaking media naivety. According to Griffiths, what sets Hereford apart is its commitment to “social engagement”. This manifested itself this year in three small local-interest exhibitions, two relating to an area of planned redevelopment in the city and one to the Hereford breed of bull; one small show on the “social issue” of disability and sport focusing on the World Blind Football Championships which took place in Hereford in the summer; a mentoring programme for local artists; and a commission to produce a socially-engaged body of work for next year’s festival, awarded to one contributor to Open Here (Jason Larkin). This strategy, fostered by the Arts Council in so many publicly-funded arts organistions to further its agenda of democratising and widening access to the arts, may be all very well, but whether it will make Hereford a must-see or must-review national and international event is open to question. In the current financial climate Hereford is perhaps lucky to have had its Arts Council grant cut by only 7% next year. Future years’ grants, however, remain to be negotiated. Funding aside, if Hereford wants to be taken seriously as a festival it needs to develop more pulling power. It needs scoops – major retrospectives or concept exhibitions that might otherwise be shown at the Barbican or the Hayward; it needs news – significant new photographic trends or talents identified through authoritative and influential curating; it should administer a substantial international prize – such as the European Publishers Award for Photography associated with the Rencontres d’Arles; and it should develop a strategy driven by ambitious photographic imperatives rather than by the politico-cultural agenda of its major funder. |

|

|---|---|