| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

FORMAT PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL Various venues, Derby

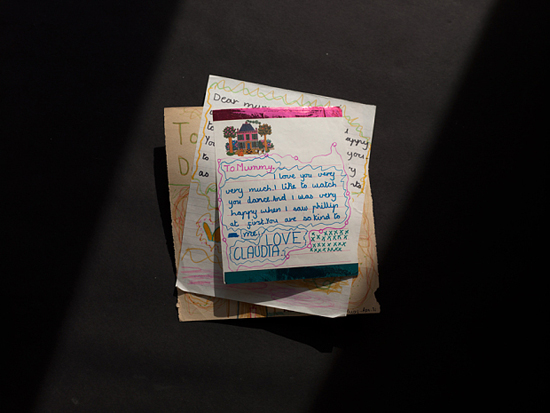

Taking ‘evidence’ as its theme, this year’s Format Photography Festival presented mini-shows of the work of some 200 photographers from around the world across 26 venues in and around Derby – an enormous range of photography relating to evidence, promising a round-up of contemporary attitudes to those age-old photographic questions: what exactly photographs can be evidence of, how far they can be trusted, what kinds of meanings can be drawn from them and why we continue to be deluded at times about what they represent. What seems clear from this Festival is that there is no dominant contemporary position but that photographers are adopting as many different stances towards the matter as ever, including some slightly disturbing new ones. The work on show can broadly be categorised as follows: 1. Documentary projects of traditional type, which present photographs as packets of data marshalled in support of a particular argument expressed in accompanying text. 2. Documentary photographs whose meaning is explicitly shown to be multi-faceted and unstable. 3. Documentary-looking photographs presented in a confusing manner without adequate context, or in very incomplete series, or both. 4. Photographs constructed to be puzzling as to what they represent or how they were made. 5. Photographs made as pseudo-evidence – explicit ‘fakes’ – through computer manipulation, staging or collage. 6. Metaphorical or otherwise suggestive photographs which disclaim any evidentiary application. This range, of course, far from being tightly themed, covers virtually all known forms of photography and examples from all six categories are jumbled together across the various venues in a pluralistic bonanza. The Festival’s main exhibition at the Quad arts centre, Beyond Evidence: An Incomplete Narratology of Photographic Truths, takes an overtly combative approach. We are promised photographers who ‘explore, question and undermine our preconceptions’ about the photograph’s reputation as a straightforward carrier of fact, and who ‘interrogate the relationship between image and knowledge’. Here as elsewhere we see a range of work but the dominant approach is what seems to be intentional destabilisation (my categories three and four). Two examples must suffice. Cristina de Middel, who made her name in 2012 with the fact-fiction blend Afronauts, shows similarly blended work from her series Jan Mayen, which we are told references a group of failed polar explorers. Minimal contextual information is given but we see what appear to be genuine Edwardian photographs of people in boats and northern landscapes and modern re-enactments (the distinction is often not clear), and diagrams, photographs and drawings of objects, many of them unrecognisable. Dozens of images are presented, framed, unframed, overlapping, mostly black-and-white, some colourised, covering a wall in rows; none is individually labelled. We are taken into a certain zone of subject matter and given a range of impressions but the meaning is left wide open. Adjacent to Middel’s work is Andrea Botto’s Ka-Boom. This work looks at man-made explosions, and similarly we see an entire wall covered with a collage of dozens of pictures, framed and unframed of various sizes, including images of explosions, objects, people engaged in explosion-related activities, diagrams and pages of text from instruction manuals. A vague positioning statement tells us that the work is meant to ‘speak about concepts such as time, limit and energy’, representing explosions as ‘a metaphor for the destruction of the contemporary world’. However, once again, nothing is individually labelled so we have to guess at what exactly is being represented and why. These and other displays play with, and presumably hope to make a virtue of photography’s inherent polysemy. Photography’s suggestive quality is one of its great strengths but the deliberate withholding of anchorage feels like a sleight of hand, a too-easy strategy for undermining meaning. Any meaning we might subjectively construct from such loosely defined – even intentionally confusing – work is necessarily tenuous and hard to commit to. The effect is alienating. The wallpaper-style displays further inhibit engagement in what, after a number of similar shows, begins to feel like a blizzard of white noise. Amidst all the quicksand it is a relief to step onto the slightly firmer ground of more conventional offerings. Phillip Toledano’s show at St Werburgh’s church, When I was Six, stands out. At that age, in 1974, his nine-year-old sister Claudia died. She was rarely spoken of again, but recently, after his parents’ death, Toledano discovered a box in the attic containing carefully-wrapped memorabilia: an envelope containing birthday cards, a checked baby dress, photographs of Claudia, letters from Claudia, a hand-drawn design for her gravestone. These are photographed and offered up simply: look at this, and this, and this. Not an entirely conventional documentary, the series also includes images that suggest distant planets, which we learn obsessed the photographer as a child after he lost his sister, interpreted as his desire to be elsewhere. Yet it is the objects from the attic which carry weight. So can these photographs be taken as evidence? Toledano presents them as props for an argument about family love. Of course one could question this, point out that the argument will be coloured by the photographer’s emotional experience, comment on the parents’ selection of items and the argument’s sentimental quality, and so on. However the story is anchored enough in a given context and universal experience to be comprehensible at least. One can choose to believe in it, as I do, and the experience of viewing the work is then revelatory and moving. If there is a lesson here it is that, even with a critical audience, photography has not lost its capacity for demonstration or for substantiating a case. And if we are looking for rich experiences from photography, including forms of storytelling and ideas to believe in, we can respond more readily when an artist or curator appears to have something that they sincerely wish to communicate to us, not about photographic interpretation but about life. |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|