| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

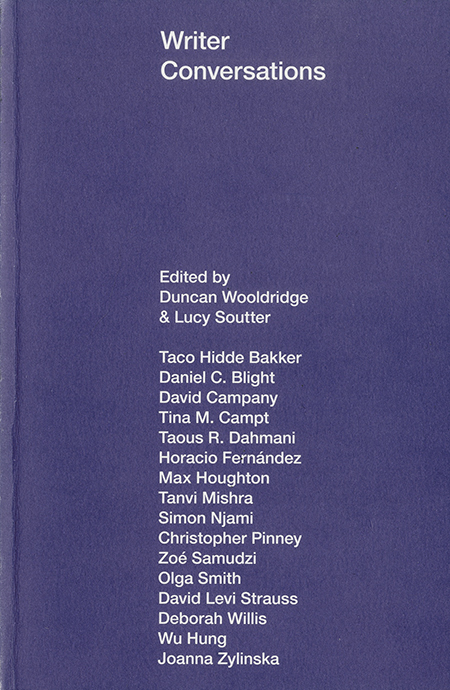

WRITER CONVERSATIONS Duncan Wooldridge & Lucy Soutter (Eds) 1000 Words, 2023 ISBN: 978-1-3999-3649-1 Pb

Although there is no shortage of published writing these days about photography, in print or online, writing about writing about photography seems relatively rare. Methodologies, processes, principles: few academic journals or magazines appear to want to discuss these matters, and where theoretical books hint at critical methods they still often draw from the rationales of the ‘cultural turn’ of the 1980/90s, even though it seems evident that there have been developments in practice and that a number of new trends are emerging. That is why this short book is so welcome and stimulating. Sixteen photography authors were sent a questionnaire, asking questions such as: what is your writing process? What questions/problems motivate your writing? What qualities do you admire in other writers? What is the significance of history/theory? Of criticality? Despite the inevitable variability and ‘raw data’ quality of the responses, the book is full of illuminating observations and provocations; and perhaps not only for those like me who write, and who try to teach students ways of writing about photography. It matters to bring what is normally tacit in critical practice into the open: it can help us recognise the zeitgeist and counter-trends, hold them up for scrutiny, and thus understand better the character and limitations of what we read. It can also highlight unexpected new ways of appreciating what photographs can be, and what they can do. It has become ‘the norm’, writes editor Lucy Soutter, for criticism now to address ‘current global concerns’ such as race, gender, ecology; the selected contributors to this book are committed to ‘engaged, ethical’ writing; and ‘the best criticism’ has an ‘itch’ to change something in art or the world. These claims about the activist/political quality of contemporary writing are supported by several contributors’ accounts of their motivations and interests: race, inequality, global violence, upending dominant systems; these and similar issues feature strongly. For all the value of such commitments, this newly dominant trend prompts anxieties about which kinds of photography and photographic experience may now be privileged for critical attention, and which discounted; and whether photographs themselves are perhaps now sometimes overlooked, or looked through rather than at, because of a preoccupation with the politics around certain types of subject matter. One contributor, Max Houghton, articulates the problem exactly: ‘Am I writing about the image or the subject matter? These concerns endure.’ Her question is left hanging. A few contributors, however, are pushing at the boundaries, exploring novel ways of writing. Some describe their desire to dwell on feeling responses; an approach that has been widely regarded as insufficiently critical in critical writing for decades. For Tina Campt, photographs ‘grab me and I get lost in them’, and her practice is ‘to linger in that experience of encounter and to share it in a way that makes others linger in the same process’. The value of taking feelings seriously may be not only experiential, but also metacognitive and revelatory. Houghton again: ‘If we take time to notice how we feel, and when we feel … we may be able to spend a little longer thinking about what matters’. Several contributors emphasise the need to slow down, and take as long as possible over the act of engagement, to allow ideas to rise and settle. One or two also point to the value of drawing on their own life history – another long-suppressed practice – to clarify why they think as they do, and to find a more authentic and holistic mode of engaging with images: ‘an embodied strategy of narration,’ writes Taous Dahmani, ‘that exists at the meeting place of gut (biography) and brain (history/theory)’. Writing, not as transcription of thought but as catalyst, even prerequisite, for thinking: ‘I write to find out what I think about things’ – this, or something similar, from three contributors. Two (only two!) emphasise the importance of writerly craft, an attention to rhyme, rhythm, words working well on the ear. ‘If you lose the music, you lose the reader,’ writes David Levi Strauss, describing writing as a ‘sculptural process’, immensely time-consuming and difficult. Several deprecate the obscurity long associated with art writing, claiming to admire clarity in others’ prose. ‘There is no need to demonstrate erudition,’ writes Horacio Fernández. I highlight here what resonates most strongly with my own interests and practice. But there is much else besides in this little jewel box of a book. |

|

|---|---|