| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

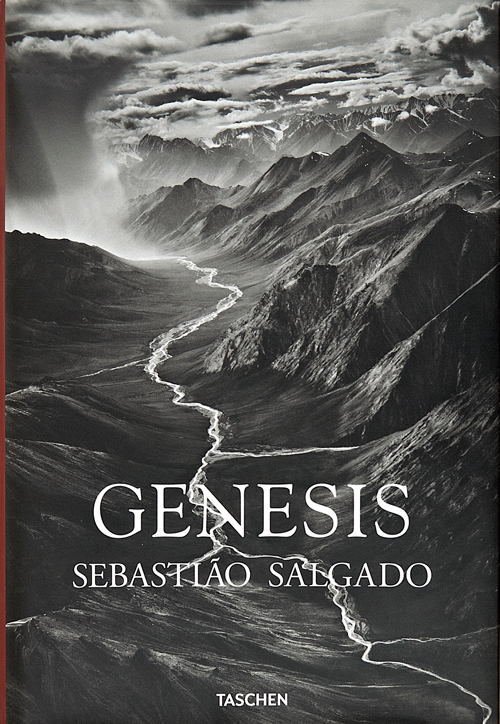

SEBASTIAO SALGADO: GENESIS Natural History Museum

Genesis is Sebastião Salgado’s ‘love letter to the planet’, as he puts it, a celebration of the ‘majesty of nature’ found in remote places and of tribal communities ‘that continue to live in accordance with their ancestral traditions’. It is also an explicit rebuke to modern ways of life that Salgado insists place the planet in peril because we no longer live in balance with our natural environment. There is nothing wrong with finding wonder in nature, or with being concerned about human impact on the planet; and Salgado has made notable efforts to bring us his message, travelling to Antarctica, New Guinea, various parts of Africa, the Amazon rainforest, Alaska, the Arctic Circle and elsewhere, supported by ice-adapted ships, canoes, light aircraft and balloons. His pictures fall into four broad categories: wide unpopulated landscapes, wildlife photographs, portraits of tribal people and – recalling the Salgado we are used to – documentary images of tribal groups going about their daily business. There are many exceptionally well-crafted images here in each of the four categories. The trouble with this show is that it is packaged in such a bombastic and facile vision of the relationship between humanity and the natural world that one cannot help but react forcefully against it. Genesis, we are told, ‘is a quest for the world as it was, as it was formed … as it existed for millennia before modern life accelerated and began distancing us from the very essence of our being.’ Leaving aside the nonsense that we are somehow looking back in time through these images, the insistent subtext is that the natural world is most impressive in regions where human impact has been lightest, where nature has not been ‘spoiled’. ‘Our planet still harbours vast and remote regions where nature reigns in silent and pristine majesty.’ Salgado has built a reputation as a humanist photographer yet this is a profoundly misanthropic message. Why should nature be regarded as less wonderful, say, in a Sussex back garden or a Greek olive grove than it is in Patagonia? The idea that nature ‘reigning in majesty’ is somehow desirable is also curious. People whose work pits them against natural forces, say deep-sea fishermen or earthquake rescue teams, might take a different view. Genesis purports to show us the ‘breathtaking beauty’ of an unspoiled natural world (‘a lost world that somehow survives’) but it does nothing of the sort. It does not show us reality, it shows us images, constructions of a modern Western mind. The values that Salgado has loaded into this work derive from a range of Romantic European ideologies and traditions of representation. His landscapes – The Grand Canyon viewed from National Forest, Arizona for example – have been composed and heavily manipulated in tonality to conform to conventions of depicting the sublime. In captions, summits are likened to jagged knives and pyramids, icebergs to cathedrals; nature is shaped everywhere in terms of human ideals and experience. Salgado’s idealisation of primitive tribes is especially troubling. Much is made of the way these groups live ‘within nature’, in some form of notional balance with it. Lives are often idyllic Chided for our modern belief that we are ‘separate from nature’, we are clearly asked to see these various groups as exemplars of a better way to live, as if one might wish to do away with the past 12,000 years of human cultural evolution. The ideal of living ‘within nature’, however, is problematic. All life-forms that live wholly within nature – from bacteria to blue whales to Japanese knotweed – ruthlessly exploit their environment to their own advantage. When humans do the same, we are at our most natural. Western societies are, in truth, no more ‘separate’ from nature than the Korowai; we simply have more power to control our environment. It is only through a sense of principled detachment from nature that we can hope to restrain ourselves from our more destructive natural instincts. Genesis is an enormous project, with 200 pictures in the exhibition and over 500 in the accompanying book. The overall effect is exhausting and numbing. For all the exquisite craftsmanship there is no punctum, nothing that stands out or surprises. There is little that has not been seen many times before in Ansel Adams, in 19th century painting, in David Attenborough, in National Geographic, in numerous examples of sweeping cinematography. Great photographs overflow with meaning, they contain more than the photographer has put into them; they do not insist on meaning, and they encourage discovery. The pictures here, by contrast, seem to have been gathered as illustrations to a theme and repeat the same message over and over. Salgado is photographic royalty; his reputation is assured. Yet one cannot help feeling that Genesis is an end-of-career folie de grandeur. A giant version of the book aimed at collectors (£7,000 for full-leather binding, delivery weight 59kg) is perhaps another symptom of this. Salgado and his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado have conspicuously claimed credit for every major role in this project: photographer, editor, writer, book-designer, curator, even ‘concept’. A slightly wider range of influential colleagues might have turned Genesis into rather more of a revelation. |

|

|---|---|