| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

F&D CARTIER: WAIT AND SEE Ffotogallery, Cardiff

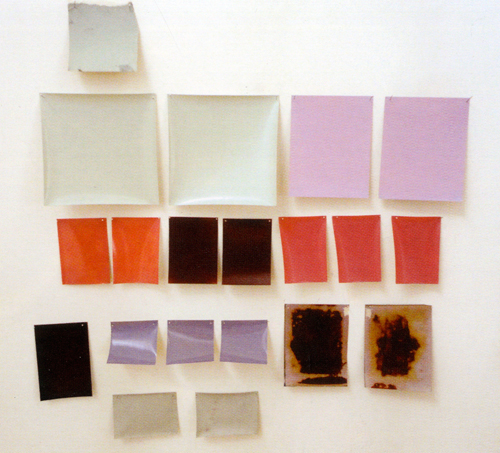

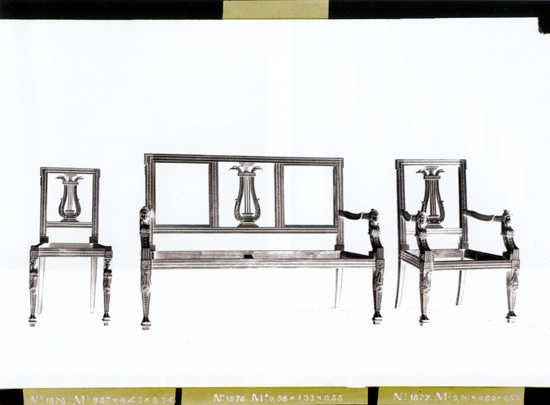

The three bodies of work by Swiss duo Françoise and Daniel Cartier presented in Wait and See: A Retrospective all involve rescue and resurrection: antique photographic materials and processes are here offered some form of new life. In doing so the works call to mind a range of issues including the adaptability of photographs and archaic photographic techniques for new purposes, the fragility of photographs as objects, the value of historic photographic materials and the nature of the medium. Addressing such matters is certainly ambitious; the challenge, however, is to find something worthwhile to say about them. The principle work in the show is Wait and See, in which various types of historic photographic paper from around the world, dating from the late 19th century to the present, are released from their ancient packaging, pinned to the wall and left to discolour slowly in the diffuse, ambient white light of the room. We are presented with a patchwork of grey, brown, mauve, purple, red, green-grey and blue rectangles, depending on the particular chemical mix of the emulsion and the age of the paper. As objects in themselves these papers prompt a certain historic curiosity: the tiny print sizes and deckle edges, for example, we know from our great-grandparents’ photo albums, or the metallic glint of bromide postcard stock, alongside the more recognisable sizes and surfaces of recent times. The invitation in the title to the visitor to stand for a few moments and watch the darkening occur, however, is a conceit: one detects no change during one visit, although gallery staff report observing a gradual darkening over the weeks. Catalogue essays by curators David Drake and Rudolf Scheutle assert that Wait and See is an ‘audacious’ commentary on the relationship between photography and time. Time is, to be sure, one of the central issues implicit in all photographic practice and there is barely a writer of note who has not commented on its complex significance. This show’s observations on time, however – photographs are made with it; and photographic materials darken with increasing quantities of it – are hardly earth-shattering. More interesting, perhaps, is its implication for the definition of photography; for these images, not being ‘of’ anything, are nonetheless photographs in the most general sense, that of surface appearances brought into being by the action of light. In this broad sense, look around, and you will find ‘photographs’ everywhere. A green field is a photograph, since it is light which draws up and greens its coverage of vegetation. Tanned skin is a photograph; as is the faded spine of a book on a shelf. To expand the definition of photography in this way is to diminish its value, of course. But if that is the game being played here, a truly ‘audacious’ exhibition might, perhaps, have mixed the Cartiers’ paper-fogging exercise with a live weblink to a Swiss meadow, a model reclining in a sun-bed (is Tilda Swinton available?), perhaps even a set of fugitive 1970s C-types fading in the same light that turns the freshly-exposed papers dark. In the second body of work, Veni Etiam, it is not ancient papers that have been given a new use, but a set of Victorian albumen glass negatives depicting furniture and chandeliers that the artists found in a Venetian flea market in 2008. The negatives, by an unknown photographer presumably working for a Venetian furniture saleroom, have been scanned, digitally coloured and printed out as large inkjets. The title, Latin for ‘Come Again’, proposed in the 16th century as a droll etymology for Venice and used ever since by the city’s hoteliers, seems wittily appropriate. The new images share in the poignancy of the originals’ pastness, and are striking enough as pictures. But is that enough? Is this a fitting end to the story of these plates, carefully made for a socially useful purpose by one of our forgotten forebears and miraculously surviving into the 21st century, to be virtualised, coloured-in and served up as art? Appropriation can be justified if it offers fresh insights, in this case into matters of time, fragility and adaptability. But to get there would have taken, perhaps, a little more ingenuity and effort. An attempt to trace and name the original photographer might have been a start. We become so locked into the transient technologies of our time that it might also have been intriguing to see photographs of modern furniture made on albumen glass, or printed on the rare antique paper arguably wasted in Wait and See. One wonders what will happen to the original plates now that they have served the Cartiers’ artistic ends. The third work here, Boys do not Cry, is the simplest, least tricksy and most affecting of the three in the show. It consists of twelve photograms, or photogenic drawings, of cotton and lace handkerchiefs in a range of pinkish hues. It is part of a much larger corpus of pink-tinged photograms of underwear, body-parts, skulls and flowers that were published in the Cartiers’ 2006 book Roses. The work could almost have been made by Fox Talbot himself, and has all the charm that one finds in any typology. The work is little more than a revival of an archaic process but is perhaps none the worse for that, as novelty is so often overrated. Its sole attempt at contemporaneity is the title. But this is a misfire: to my mind at least these delicate and nostalgic images have no such sociocultural connotations. |

|

|---|---|

|

|