| SIMON DENISON IMAGE & TEXT |

| PREVIOUS | NEXT |

REFERENCE WORKS Library of Birmingham

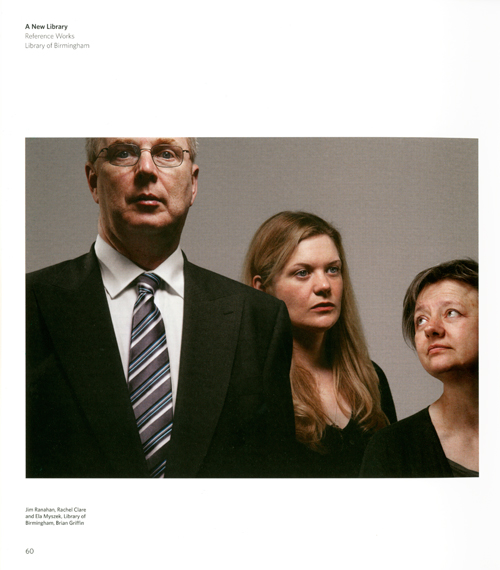

The opening of the Library of Birmingham – the largest non-national public library in Europe and home of one of the UK’s major photography collections – in an architecturally dazzling new building in September seems an emphatic public endorsement of the value of archives and libraries at a time when local libraries elsewhere face neglect and closure. Alongside the glamorous recent remodelling of Birmingham’s shopping centre and the restoration of the classical Town Hall, it also looks like another bold gesture in a civic strategy to attract investment by transforming the city’s formerly drab public image. A few hundred yards away from the new building stands the condemned former Central Library. Designed in a spirit of modernist idealism, opened by Harold Wilson in 1974 and itself the largest regional library in its day, its concrete style has fallen into deep disfavour, superficially the very embodiment of drabness despite its architectural qualities and remaining adequacy as a library. Its architect John Madin, who must have hoped his monument would long outlast him, complained bitterly to a local paper in 2011 about its premature replacement. Madin never saw the new building completed as he died the following year. Into this web of values and narratives, cultural politics and changing fashions, civic and individual aspirations and disappointment, the new library emerges; and four photographers with connections to Birmingham – Brian Griffin, Stuart Whipps, Michael Collins and Andrew Lacon – were asked to respond to its appearance for the opening show, Reference Works, at the gallery in the new building. Of the four, Whipps has tapped most successfully into the larger meanings of the new development. His work draws attention to ‘what is worth saving and why’, by focusing on fragments of the Shakespeare Memorial Room and interiors of the 1974 library. The bookcase-lined Shakespeare Room is a relic of the Victorian library which preceded Madin’s building, taken down and reconstructed twice in succeeding libraries; it now forms the top floor of the new building, the ‘golden hatbox’ on the library roof. The modernist library, meanwhile, is destined to be recycled as hardcore, the images of its decorative details now more valuable culturally than the building itself, as Whipps notes in a recorded interview shown as part of the exhibition. Whipps stresses, and his pictures demonstrate for those with eyes to see, the elegance of the modernist structure, and the ways in which its occupants undermined its design through adaptations in daily use. Truly we were never the giants the modernists hoped we might become, just flawed humanity in need of our partitions and a spot of colour. His exquisitely composed photographs aestheticise what is being presented as a botch, and thus undermine his case a little. Nevertheless his observation about the ‘resonance’ of showing these pictures of the old building inside the new rings true: they attend like a dignified former president, ousted on trumped-up charges, at the celebratory inauguration of his successor. Lacon also refers to the old and new library buildings in elaborately coded work that addresses the relationship between photography and sculpture. Starting, it seems, from the premise that buildings and other types of subject are often represented as sculpture, bits of library and building materials are remodelled as sculptures in his studio, the sculptures are photographed and displayed as either sculptures or photographs, while photographs are presented as sculptures. The work is clever; and some of it quite striking. His modelling of a pallet of building blocks in various stages of unloading is well seen and realised. If Lacon’s cool intellectualism belongs in the thought-world of the old library, Griffin’s show has all the fizz of the new. Griffin is one of the most consistently inventive of British photographers, and his group portraits of people involved in the library project seem entirely fresh. His theatrically-lit and staged pictures recall a range of painting and figurative sculpture styles, and the best suggest some urgent narrative. Jim Ranahan from the library is presented, tense and monumental, as if about to embark on some fateful quest, while a colleague looks up with nervous admiration. Another group in white coats, presumably conservators, gaze down at a glowing specimen, while one stares directly at camera with a mournful gaze. She knows something it seems; but what? The pictures, however, provoke a certain unease. The stories they suggest are Griffin’s stories, fabrications made in the cause of artistry. His subjects appear drained of themselves. Many have been persuaded to play the fool in surrealistic set-ups with props such as teacups, a rock and an Elizabethan ruff. Too much portraiture is puffery, of course, and we all know that no lens is sharp enough, no shutter speed short or long enough to capture so complex and volatile a thing as personality. So what is a portrait? Why bother? Griffin’s work seems to find refuge from this conundrum in playful cultural referencing, despite his claim to be recording his subjects for history. Yet some truth can be recorded in an uncontrived portrait, polysemy can be anchored in a measure of fact; this is the photographic path to meaning and sitters can perhaps retain a little dignity in the process. Novelty is not necessarily the highest virtue. Alongside Collins’ record pictures of the construction site, the exhibition also presents archive images of Birmingham’s previous libraries, including the Madin library when new and its Victorian predecessor with a reading room like the interior of a cathedral. Much has been lost; but for photography at least the story goes on. In addition to the gallery and the graduate mentoring programme that formed part of Reference Works, the new library has established GRAIN, a ‘development hub’ for the medium. Behind the glitter of the new building’s façade there appears to be a will to create something substantial with photography in a region that remains undernourished by first-rate experiences of contemporary art. |

|

|---|---|